Science重磅成果:给CAR-T多加个“A”,不治癌症,治自身免疫疾病!

2016/7/3 0:29:06Science 世界医疗科技资讯

导读

6月30日,发表在Science上的一项研究中,宾夕法尼亚大学Perelman医学院的科学家们找到了一种治疗自身免疫疾病的方法,这一新技术最重要的特点是不会损害免疫系统的其它部分。值得注意的是,该技术是对热门癌症免疫疗法CAR-T的一种新改造。

6月30日,发表在Science上的一项研究中,宾夕法尼亚大学Perelman医学院的科学家们找到了一种治疗自身免疫疾病的方法,这一新技术最重要的特点是不会损害免疫系统的其它部分。值得注意的是,该技术是对热门癌症免疫疗法CAR-T的一种新改造。

领导该研究的Michael C. Milone博士说:“我们的研究有效地开辟了CAR-T技术更广泛的应用,包括对抗自身免疫性疾病、移植排斥反应。”

目前治疗自身免疫疾病的方法主要是大范围抑制免疫系统,这会使患者更易受到感染和癌症的攻击。这一研究中的新技术成功地在小鼠模型中治疗了致命的自身免疫性疾病,且无明显的脱靶效应。

Aimee S. Payne博士是该研究的通讯作者之一,致力于自身免疫相关的研究。几年前,她实验室的博士后研究员Christoph T. Ellebrecht对利用CAR-T技术作为一种潜在的“武器”治疗B细胞相关自身免疫性疾病产生了兴趣。Milone说:“我们认为,我们能够改造这一技术,使其特异性地杀伤那些通过产生抗体引发自身免疫性疾病的B细胞。”

新型CAAR-T技术

在这项新研究中,科学家小组研究的是一种称为寻常天疱疮(pemphigus vulgaris,PV)的自身免疫性疾病。据悉,PV患者的B细胞会产生抗体攻击一种名为desmoglein-3(Dsg3)的蛋白,它的作用是使皮肤细胞粘附在一起。如果不治疗,PV会引发大范围的皮肤水泡,几乎是致命的。

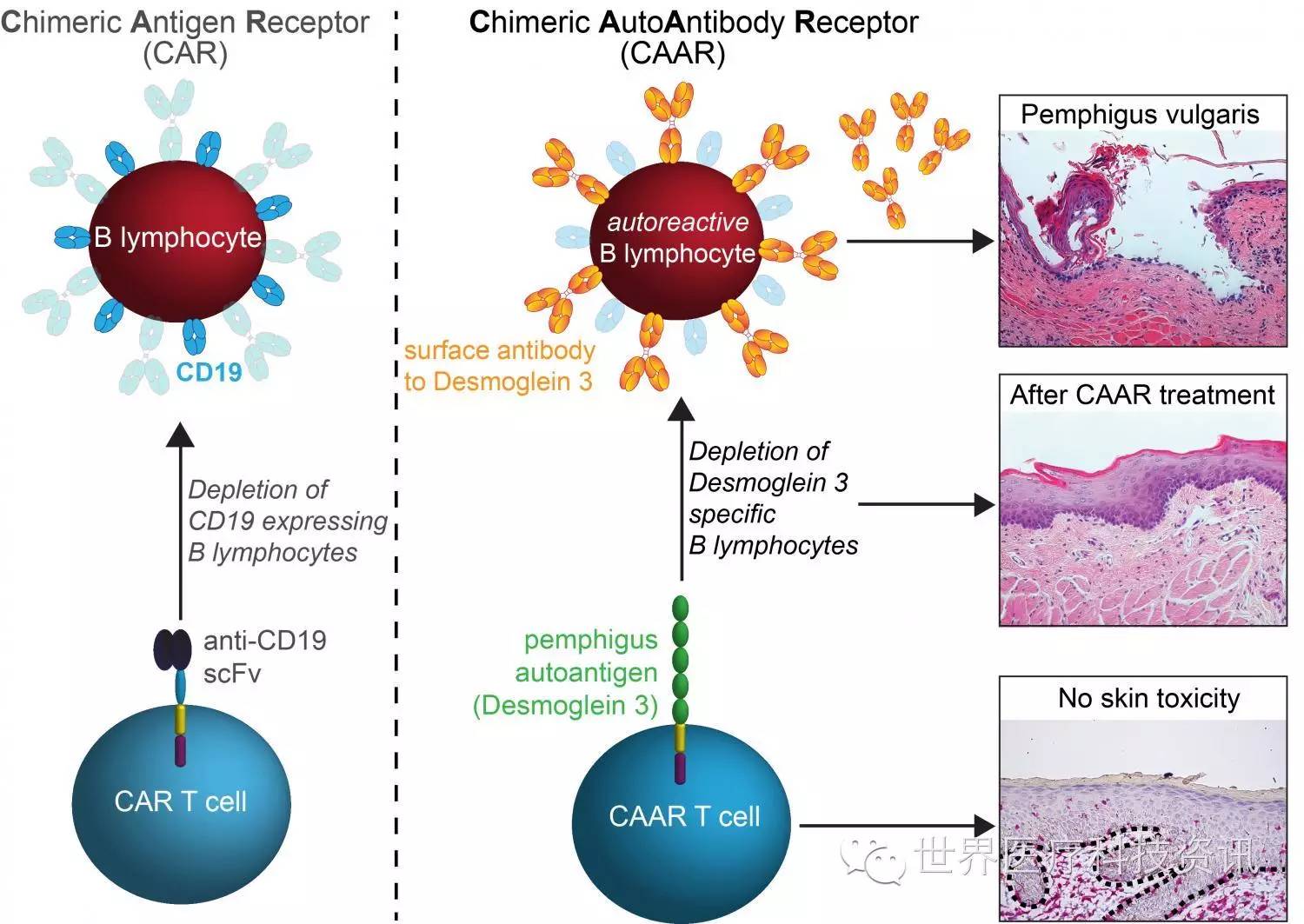

为了能够实现在治疗PV的同时又不引发广泛的免疫抑制,宾夕法尼亚大学的科学家小组设计了一种新型CAR受体,能够指挥患者的T细胞只攻击产生有害抗Dsg3(anti-Dsg3)抗体的B细胞。

研究小组开发了一种嵌合自身抗原受体(chimeric autoantibody receptor,CAAR),其包含了自身抗原Dsg3的片段。CAAR的作用是吸引靶向Dsg3的B细胞,最终被T细胞杀伤。此外,小鼠研究中,没有任何迹象表明这种工程T细胞会因脱靶效应产生副作用。

未来研究方向

目前,研究小组计划在狗身上测试这一疗法。据悉,狗也会患PV,且经常死于该疾病。Payne表示,如果我们能够利用CAAR-T技术安全地治愈患PV的狗,这将是兽医领域的突破,也将为在人体中测试该疗法铺平道路。

Milone在接受BBC采访时表示,这类技术也有望用于一些相似的疾病(病因与一种抗体明确相关),如重症肌无力。然而,其它一些自身免疫性疾病的病因非常复杂,如红斑狼疮、1型糖尿病以及多发性硬化症,因此不容易治疗。

对于这一新进展,British Society of Immunology的Danny Altmann教授说:“CAR-T细胞技术是一项很出色的创新。这项研究很有创意,且相当成功。”然而,他也警告称,最终形成的治疗方案可能会非常昂贵。

原文阅读?

New therapy treats autoimmune disease without harming normal immunity

In a study with potentially major implications for the future treatment of autoimmunity and related conditions, scientists from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have found a way to remove the subset of antibody-making cells that cause an autoimmune disease, without harming the rest of the immune system. The autoimmune disease the team studied is called pemphigus vulgaris (PV), a condition in which a patient's own immune cells attack a protein called desmoglein-3 (Dsg3) that normally adheres skin cells.

Current therapies for autoimmune disease, such as prednisone and rituximab, suppress large parts of the immune system, leaving patients vulnerable to potentially fatal opportunistic infections and cancers.

The Penn researchers demonstrated their new technique by successfully treating an otherwise fatal autoimmune disease in a mouse model, without apparent off-target effects, which could harm healthy tissue. The results are published in an online First Release paper in Science.

"This is a powerful strategy for targeting just autoimmune cells and sparing the good immune cells that protect us from infection," said co-senior author Aimee S. Payne, MD, PhD, the Albert M. Kligman Associate Professor of Dermatology.

Payne and her co-senior author Michael C. Milone, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, adapted the technique from the promising anti-cancer strategy by which T cells are engineered to destroy malignant cells in certain leukemias and lymphomas.

"Our study effectively opens up the application of this anti-cancer technology to the treatment of a much wider range of diseases, including autoimmunity and transplant rejection," Milone said.

The key element in the new strategy is based on an artificial target-recognizing receptor, called a chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR, which can be engineered into patients' T cells. In human trials, researchers remove some of patients' T cells through a process similar to dialysis and then engineer them in a laboratory to add the gene for the CAR so that the new receptor is expressed in the T cells. The new cells are then multiplied in the lab before re-infusing them into the patient. The T cells use their CAR receptors to bind to molecules on target cells, and the act of binding triggers an internal signal that strongly activates the T cells—so that they swiftly destroy their targets.

The basic CAR T cell concept was first described in the late 1980s, principally as an anti-cancer strategy, but technical challenges delayed its translation into successful therapies. Since 2011, though, experimental CAR T cell treatments for B cell leukemias and lymphomas—cancers in which patients' healthy B cells turn cancerous—have been successful in some patients for whom all standard therapies had failed.

长按二维码扫描关注

http://weixin.100md.com

返回 世界医疗科技资讯 返回首页 返回百拇医药